Glass Bottle Manufacturing In Milwaukee by Marty and Donna Kupferschmidt

Several glass factories, mostly along the Fox River and Lake Michigan, where sand was available to make the "gummy metal," were started...and failed in Wisconsin. One such small factory, that made window glass, sprouted up in Omro in 1876. It failed the following year.

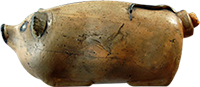

No other glass factories were in existence in Wisconsin until the beginning of 1880, when Enoch Chase set up plans to build a factory in Bay View to produce bottles for local breweries. He built The Bay View Works, which housed two melting units, on his farm near the southern limits of Milwaukee, which was at Lincoln Ave. Dr. Chase retained full ownership of the smaller furnace, while the Chase Valley Glass Co. No2, a corporation, owned the larger. Capitalization of the firm was $24,000. The corporation had authority to make glass and glassware of all kinds, as well as to sell and trade the products. Dr. Chase was president and held a controlling portion of The Bay View Works' stocks. By late August, skilled workers from the East started to arrive and management took out ads in The Sentinel, urging neighborhood children to bring in old and broken glass to The Bay View Works to glaze melting pots and quicken fusion of the glass batch. The first glass produced was on September 1, 1880, as large crowds gathered to watch. According to The Sentinel reports, 13,000 bottles were produced daily and, at the annual "fire" or blast, 3,000,000 bottles were produced. Though these numbers aren't great by today's standards, to get those numbers by hand-blowing, all workers had to work very hard under 2600 degrees of heat. Hard and hot work was rewarded with good pay, as glass workers received good wages compared to other occupations.

"Dr. Enos Chase, proprietor of the Chase Valley Glass-works, was mad yesterday. Mad hardly expresses it. Some of the workmen wanted a holiday and so they slyly put fresh sand in the working crucibles, which compelled a shutting down of the works until the additional sand melted." (#1)

After one year of operation, The Chase Valley Glass Co. #2 reorganized to become the Wisconsin Glass Co. with a capital investment of $30,000. With this reorganization, Guido Pfister, a well-known Milwaukee businessman, succeeded Chase as president.

"The buildings of the Wisconsin Glass Company, on Lincoln avenue, cover a large tract of ground and are very conveniently arranged near the railway tracks. Only three years ago, this same piece of land was a swamp, but now it has been graded and resounds with the hum of busy industry. The Company only manufactures bottles, but these bottles range all the way from a two-ounce apothecary's bottle to a sixteen-gallon carboy. With W.E. Slimm, a son of the superintendent, for a guide, a reporter for The Sentinel yesterday made a tour of the works.

The first thing done is the manufacture of the huge "melting pots" in which the glass is melted. They are made from German fire-clay and will hold one ton of molten glass. The clay is obtained from Germany and is carried as ballast by the vessels which bring it here. The clay is mixed with water until it has arrived at about the consistency of dough. It is then laid out upon the floor, which is kept scrupulously clean, and further mixing is done by boys who tramp upon it with their bare feet. This is kept up for about three days and then the clay is ready for molding. After the feet get through, the hands come in for their share of the work, for all of the molding is done by hand. The bottom is first laid on a layer of gravel, this being necessary as when it shrinks the gravel moves and the shrinkage is equal. When completely molded they are allowed to slowly dry, this drying process taking about four months. They are then placed in the furnaces by means of a huge machine with an iron tongue on which the pots are hung. The fires of the furnace are burning very low when the pots are first put in. The mixture of lime, soda, salt, etc., of which the glass is made is then put in and the fires are gradually increased. Hotter and hotter the fires become until everything in the furnace is at a white heat, until the temperature nearly approaches 3000 degrees, and in the shade at that. It is during the night time that the melting is done and at 7 o'clock in the morning the gang of glass-blowers come on. Each furnace contains ten pots and there are three large furnaces. Two men and one gathering boy work at each pot. The process of blowing the bottles is an interesting one. A number of long hollow iron tubes are arranged in a rack. The boy takes one of these and plunges it in the molten glass. A large chunk adheres to it and the boy then draws it out and wipes the tube with a sponge. The man then seizes the pipe and rolls the lump upon a stone in front of him. After rolling it until there is no air in the glass, he blows into the tube and then, after a few swings, drops it into an iron mold which is fastened at the bottom of a platform on which he works. With a lever, worked with his foot, he closes the mold and blows into the tube. The result is that the glass is blown out into the shape of the mold. With a motion of his foot he opens the mold and draws up the bottle, which is minus a neck. Another workman picks up the red-hot glass with a pair of large pincers, places the bottle in a last, and with a few turns, the neck is formed and a perfect bottle is rolling around in a hollow iron tablet, on which it is thrown. A dirt-begrimed boy, armed with a two-pronged fork, and looking like a miniature demon, rushes up, and in an instant the bottle is in the annealing oven. The fire in the annealing oven is kept at about the temperatures of the red-hot glass until evening, when it is allowed to die out, thus cooling the bottles gradually. The entire process of blowing and molding consumes but a fraction of a minute, and two men and a boy make about ninety-five dozen quart bottles in one day. The journeymen glass-blowers were all healthy-looking men, some old, others quite young, and seemed not to mind the heat in the least.

"What are the men paid per week?"

"Oh, they are down-trodden working men. They only make from $30 to $45 a week, and, they have got one of the strongest unions in the country. It made me tired to read Congressman Guenther's speech about any tariff on glass bottles coming out of the ‘poor, down-trodden workingmen.' Why, German manufacturers can undersell us right here in Milwaukee, but," added the young man, "they can't make better bottles."

"Whom do you sell to?"

"We ship all over the Northwest and sell a great many in Milwaukee to the manufacturers of bottled beer." From which, taking everything into consideration, the works, the quality of the glass and prices, which are low, ranging according to the size of the bottles, it is to be inferred that Milwaukee may well congratulate herself on her glass manufacturing industry." (#2)

Under Pfister, capitalization grew, gradually, up to $150,000 in 1885. Pfister, during this period, added a third furnace. This furnace allowed the annual output to increase to 50,000 gross and expanded glass production to include table glassware, fruit jars, prescription, beer, cider and ink bottles, pocket flasks, carboys and window panes. Available colors were amber, dark, green or blue. At that time, blue glass was thought to possess special curative properties for plant and animal life and growth.

The diversification of product marked the start of The Wisconsin Glass Co.'s collapse. In order to be profitable, a glass company needed to specialize in a product. The second threat to the livelihood of The Wisconsin Glass Co. was its out-of-state competition's access to cheap fuel, natural gas, which allowed them to undersell The Wisconsin Glass Co. Thirdly, and most damaging, were a series of strikes about wage cuts and disagreements beginning in 1885 and culminating in the labor upheavals of 1886 in Bay View. As a result of the wage negotiations of the window glass workers, the window house was down for a part of the 1885 blast in September. After that, production slowed down considerably.

"About 100 glass-blowers find employment in Milwaukee and Bay View. The works of the Wisconsin Glass company on Lincoln avenue are primarily an American green-bottle concern, while the Standard Art Glass works in Bay View manufacture stained glass for windows and articles for the table. Green glass is less expensive than flint glass, which is absolutely colorless. The former, too, is without color when its density and mass is slight, but even in a common window pane the edge distinctly reveals the tint of the sea. It is principally blown into bottles of every variety and shape, beer bottles for the brewers predominating. The substances which form the basis of all varieties of common glass are silica as the acid element; soda or potash as the alkaline base, and lime and oxide of lead as the alkaline earths. To the latter ought to be added baryta and alumina, the former being used in the place of lead, and the latter being a common ingredient in certain kinds of glass.

The melting pots are made of the finest clay, great care being necessary in the selection, as the presence of any foreign particles will injure the crucible. A fine powder procured by grinding old pots is generally mixed with virgin clay. The ingredients are worked into a paste in a large trough, and afterwards trampled upon until the admixture becomes as tough as putty. It is then made into rolls and wrought, layer upon layer, into a solid and compact body, which shrinks about two inches in drying. In the construction of a furnace the principal objects to be kept in view are the production and maintenance of an intense heat, and its uniform distribution throughout the oven. The form is generally square or oblong and circular.

Bottle glass varies in tint from the dark green, almost black, to the semi-transparent claret bottles to clear and transparent qualities. The materials ordinarily employed are common sand, gas-lime, brick clay, common salt and soap-boilers' waste. In a common bottle house the furnace is oblong, and is erected in the center of the brick cone, above a cave, which admits the air to the grating. The working holes of this furnace, opposite each pot, for putting in the materials and taking out the liquid glass, are each about one foot in diameter. At each angle of the furnace there is also a hole about the same size communicating with the arch and admitting the flame from the main furnace.

After the metal has been skimmed, the person who begins the work is the gatherer, who, heating the pipe, gathers on it a small quantity of metal. This pipe or blowing tube is of iron about seven feet long. After allowing the first dip to cool a little, more is gathered until there is sufficient for one bottle. The gatherer then puts the metal into a brass or cast-iron mold of the shape of the bottle wanted, and, continuing to blow through the tube, brings it to the desired form. The blower then hands it to the finisher, who touches the neck of the bottle with a small piece of iron dipped in water, which cuts it completely off from the pipe. He next attaches the punty, on which is a little metal gathered from the pot, to the bottom of the bottle, and thereby gives it the shape which it usually presents. The finisher then warms the bottle at the furnace, and taking out a small quantity of metal on what is termed a ring iron, he turns it once round the mouth, forming the ring seen at the mouth of bottles. He then employs the shears to give shape to the neck. One of the blades of the shears has a piece of brass in the center, tapered like a common cork, which forms the inside mouth; to the other blade is attached a piece of brass, used to form the ring. The bottle is then lifted by the neck on a fork by a boy, and carried to the annealing arch, where the bottles are placed in bins above one another. This arch is kept a little below melting heat, till the whole quantity, which amounts to ten or twelve gross in each arch, is deposited, when the fire is allowed to die out.

Sheet-glass making involves the blowing of the cylinder and the opening and flattening of the glass. Radiating from the work holes and raised about seven feet above the floor, are long stages with an open space between each to allow the workman to swing about his long tube in forming the elongated cylinder of glass. When the metal is ready, the blowers take their stations, each having his own pot and also an assistant. After gathering about twenty pounds of metal, the workman places it in a horizontal position in the large hollow of a wooden block, and turns it into a solid cylindrical mass. In the meantime, the assistant, with a sponge in his hand, and a bucket of water by his side, lets a fine stream of water run into the block, which keeps the wood from burning, and also gives a brilliancy to the surface of the glass. The water, the moment it comes in contact with the glass, is raised to the boiling point, and in that state does no injury to the metal. But it is only when the metal is at a high temperature that such is the case; for whenever the glass is cooled to a certain degree, it immediately cracks upon coming in contact with water.

When the workman perceives that the mass of metal is sufficiently formed and cooled, he raises the pipe to his mouth at an angle of about 75 degrees, and commences blowing it, at the same time continuing to turn it in the wooden block, till he perceives the diameter to be of the requisite dimensions, which are usually from eleven to sixteen inches. The workman then reheats the cylindrical mass, and when it is sufficiently softened commences swinging it over his head, continuing to reheat and swing till he has made it the desired length. The ends of the cylinder are cut off, and then the tube is ready for flattening.

To accomplish this the practice is either to lay the cylinder horizontally on a bench, and draw a red-hot iron two or three times along the inner surface, or to split it with a diamond cutter fixed in the cleft of a stick and guided from end to end by a straight edge. The cylinder is then taken to the flattening kiln, and placed in the oven with the split side upwards. In a short time it becomes softened by the heat, and by its own weight falls out into a flat, square sheet. The flattener, with a piece of charred wood, rubs it until it is quite smooth, and then places it on edge in the annealing arch, where it remains about three days.

Colored glass is produced by adding small quantities of various metallic oxides and other mineral substances, while the ordinary materials are in the melting pot. Blue is obtained by the use of cobalt; yellow by uranium and salts of silver; green by oxide of chromium; red by cuprous oxide; ruby, carmine and pink by a compound of gold with a tin oxide. Colored sheet glass may be either composed of pot metal or it may be of "flashed colors." Pot metal consists of glass uniformly colored throughout, while in flashed colors the body of the glass is transparent sheet metal, covered on one surface only with colored glass. (#3) The labor tensions of 1886 shut The Wisconsin Glass Co. down completely.

In 1888, Arthur P. Ayling, an experienced glass maker from Ohio, became president of an entirely new corporation called Cream City Glass Co. The Cream City Glass Co. leased part of the factory for the specializing in beer bottle production, with capitalization at $20,000. In 1891, its capitalization stood at $50,000. By 1892, Cream City Glass Co. enjoyed much success. It's output of glass bottles and fruit jars had a market value of $237,000. Cream City Glass Co. employed 260 people, with total wages of $117,000.

Success died, however, in 1893 with the Depression. The Depression caused a sharp decline in all phases of glass manufacturing in Milwaukee. The Cream City Glass Co., despite its boom years of 1888 through 1892, could not recover and was taken over in 1894 by the Northern Glass Co. Former president Ayling became the treasurer. This new firm, incorporated at $200,000, could purchase, sell or lease formulas and processes for glass making, as well as actually manufacture and sell glassware. This corporation lasted only two years, however, because of inferior or worthless bottle manufacturing due to the use of iron slag as a batch ingredient. This problem, pondered by Mrs. Ayling, was brought to William R. Franzen.

Franzen became president of Northern Glass Works on June 18, 1896 with a capitalization of only $10,000. Arthur and Cora Ayling were co-incorporators. To become successful, Franzen enlisted the help of glass makers to produce a quality product of "soft metal" (glass). No more iron slag was used to produce glass.

Under Franzen, Northern Glass Works soon exceeded the success of any of its predecessors. When it was reincorporated in 1900 as Wm. Franzen & Son, the firm's capitalization rose to $300,000. Although skilled hand gatherers increased the production costs, the use of cullet in the batch reduced operation costs. Through the use of semiautomatic machines and recently developed tank furnaces, the annual output of bottles reached 300,000 gross. Milwaukee brewers were the largest purchasers of Franzen bottles; other brewers bought them as well.

Unfortunately, Prohibition put an end to Wm. Franzen & Son. Makers of near beer and soda and contractors of home brew could not keep them afloat. Dissolution of Wm. Franzen & Son, by a unanimous vote of 600 shares, came on December 24, 1921. The glass bottle industry of Milwaukee came to an end.

Bibliography

Historical Messenger of the Milwaukee County Historical Society, September 1962, "The Glass Bottle Industry of Milwaukee, A Sketch," by Edward Noyes, pages 2-7.

- The Sentinel: Milwaukee, December 2, 1881

- The Sentinel: Milwaukee, February 10, 1883

- The Sentinel: Milwaukee, April 11, 1886