Chase Valley Glass Company by Peter Maas

The opening Chase Valley Glass Company marked the beginning of a 30-year era of glass manufacturing in Milwaukee. Although the Chase Valley works operated only one brief season, four successive glass works operated at the same location. The Chase Valley glass works also left behind a rich legacy of bottles and flasks for collectors.

COMPANY HISTORY

When Vermont native Dr. Enoch Chase settled at the site of present day Milwaukee in 1835, he was one of the first whites in the area and was Milwaukee's first practicing physician. Dr. Chase lived in Milwaukee and practiced medicine until the 1870s when health problems forced him to give it up his medical practice. In 1876, he and his son George started a brick manufacturing business on his farm at the southern city limits making Milwaukee's famous cream-colored brick. About the same time, a former Pittsburgh glass factory manager approached Dr. Chase about starting a glass factory in Milwaukee. The proposition seemed to make a great deal of sense. There was tremendous demand for glass bottles and no local producers. The Chase farm was in an ideal location near rail and water transportation. In addition, the two key ingredients needed for glass production, sand and fuel, also happened to be key ingredients used in brick-making.

In March of 1880, Dr. Chase announced that an analysis of the sand found near the Milwaukee harbor showed that it consisted of 60% silica, making it suitable for glass making. He also announced that he had managed to build an experimental furnace and showed samples of clear glass bottles that he had produced using the local sand. Dr. Chase said that it was his intention to build a glass bottle factory on his property directly south of his brick works.

Dr. Chase's marketing strategy would be to target mainly the brewing industry. He estimated that the Milwaukee breweries alone purchased over 8 million bottles annually. While he believed that there was other potential business besides beer bottles, Dr. Chase felt that the brewing industry offered the greatest immediate opportunity. Milwaukee brewers had established highly effective marketing networks to sell bottled beer nationally and even internationally. With the recent adoption of pasteurization, the bottled beer business in Milwaukee was booming.

Construction began almost immediately, and by May of 1880 was nearing completion. The works consisted of two separate business entities housed in separate buildings. The first company was Chase Valley Glass Company No. 1. It was located in the south building and had a 4-pot furnace, which the Milwaukee Sentinel described as "experimental" in nature. Dr. Chase owned 100% of this company. Company No. 1 employed two of Enoch's sons, Clarence and Clifford, along with eight blowers and thirty other men and boys.

The second company was Chase Valley Glass Company No. 2, which was located to the north of Company 1. It had a coal-fired furnace with 8 pots, each with a capacity of 1800 to 2000 pounds of glass. It had a specially design that used less fuel than conventional furnaces of that time – an important competitive advantage.

Chase Valley Glass Company No. 2 incorporated on August 2, 1880. Dr. Chase owned a controlling interest in this firm. Other owners included Guido Pfister and Fred Vogel (co-owners of a nearby leather tanning business) and C. J. Meyer. The Plant Superintendent was Joseph Slimm, who had previously worked at the Pittsburgh based A. & D. H. Chambers glass works for a number of years. He had also served as superintendent of the A. J. Mansfield glass works in Lockport, New York. The Fireman was Joseph Jones. Company No. 2 employed 16 blowers and 35 others.

The typical glass blowing season, or "blast," ran from September thru June, because as the Sentinel puts it, "the blowers will not work during July and August." By the end of July, Joseph Slimm returned from a recruiting trip to the east (probably Pittsburgh) with the last of the experienced glass workers needed to start up the plants. Most of the experienced managers and blowers had already been hired and brought to Milwaukee.

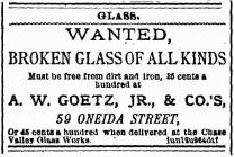

In August, an advertisement began to appear daily in the Milwaukee Sentinel, offering to pay 45 cents per hundred pounds of glass delivered to the Chase Valley works, to be used for cullet to glaze the new pots. Children were also encouraged to gather broken glass.

In August, an advertisement began to appear daily in the Milwaukee Sentinel, offering to pay 45 cents per hundred pounds of glass delivered to the Chase Valley works, to be used for cullet to glaze the new pots. Children were also encouraged to gather broken glass.

The opening of Dr. Chase's glass works on September 1 attracted hundreds of visitors, including local business representatives as well as many women and children. According to the Milwaukee Sentinel, “Not much real work was done on the first day of regular production as blowers spent much of their time entertaining visitors and creating souvenirs such as Jacob's Ladders, canes, soup ladles and other fancy items for visitors to take home with them.”

The furnaces burned 24 hours a day, but bottles were produced only during the day, starting at 7:00 A.M. Blowers worked in pairs, one pair per pot. Standing on a platform, one worker would withdraw a small gather of glass with a 5- foot blowpipe. He would blow to expand the gather slightly, and then would roll it on a rough marble slab to shape it for the mold. The blower placed it into the mold, closed it, and then blew vigorously for a few seconds. The mold was opened and the bottle withdrawn. The lip was applied and the bottle was placed in the annealing oven, where it was gradually cooled over a 24-hour period.

Blowers were paid by the piece, and made an average of $6 to $7 per day, which at the time were excellent wages. The factory was extremely hot, and the workers were "wet as drowned rats" according to the Sentinel. Combined capacity for the glass works was about 13,000 bottles per day, or 3,000,000 per season. The bottles sold for between 6 and 8 cents each.

Company No. 1 brought its sand from Greenfield, Wisconsin, while Company No. 2 brought sand in ships from the opposite shore of Lake Michigan. The other necessary ingredients were imported from the east, including soda ash, salt lime, and colorizing agents.

When factories 1 and 2 opened, there were plans to immediately build a third bottle factory, and possibly a forth dedicated to window glass. Plans called for the third factory to be completed by October 1, 1880. However, for unknown reasons it did not materialize.

In early November, just three months after opening, Factory No. 1 closed temporarily pending resolution of a dispute over furnace design patent royalties with a Mr. Johnson. Dr. Chase settled the claim out of court and installed the new furnace technology in Factory 1. It was already used in Factory 2. By December 3, the remodeling was finished and Factory 1 was back in production.

The glass works operated without major incident through winter and spring. The Sentinel noted that there were many visitors to the plant, that production consisted mainly of beer bottles and fruit jars, and that it was running at full capacity. In May of 1881, Dr. Chase announced that the third factory would be build immediately, but again it did not happen.

In July of 1881, the Chase Valley works closed for the summer. Dr. Chase retired from the glass making business, selling Company 1 as well as his interest in Company 2. On August 16, after only one 9-month season of operation, the two companies reorganized, combining into a single entity called the Wisconsin Glass Company. The company's former vice president, Guido Pfister became president, and C. J. Meyer and Joseph Slimm stayed on as vice president and plant superintendent.

It is unclear if Dr. Chase’s reasons for selling were personal, financial or otherwise. However, he was 72 years old, he was suffered from health problems, and had other business interests to attend to, so it is quite possible that he simply decided to retire. Evidence does not suggest that the venture had failed. The Wisconsin Glass Company continued in the same facilities, with the same management and initially produced mostly beer bottles, although they later diversified the product line. The only apparent difference between the old firm and the new was the new name and the absence of Dr. Chase.

COLLECTING THE BOTTLES

Many examples Chase Valley Glass bottles have survived. Most are bottom embossed, and the great majority of specimens include the "2" designation. Undoubtedly, many of the Chase Valley bottles were unmarked, such as fruit jars and turn mold bottles. Most Chase Valley bottles did not carry a mold number, which became a common practice of the Wisconsin Glass Company, probably for quality or inventory control purposes. The Wisconsin Glass Company may actually have produced some bottles marked Chase Valley, since it was a common practice for glass companies to continue using old molds, sometimes without reworking them.

Typical bottom embossing includes C.V. No, 2 MILW, C.V.G. Co. No. 1 MILW, C.V.G. Co. MILW, C Co. 2 MILW, and C MILW. Most also have a numeric or alpha mold identifier in the center on the bottom. Mold numbers for factory 2 range from 1 to 23, and I have seen letters as high as W.

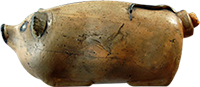

The most common bottles from factory 1 are coffin flasks that usually found in aqua and light shades of green and olive green. These flasks tend to be very crude, including the mold markings. There are also some examples of amber beer bottles from Factory 1 (see illustration). Some Chase Valley bottles do not have a factory designation, and could have been produced by either factory. Examples include beer bottles from brewers Charles Gipfel, E. L. Husting, and Louis Werrbach.

A twenty-gallon display bottle was blown for the Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce. It is unlikely that this bottle survived, but it was undoubtedly free-blown and unmarked.

Most of the bottles were amber, aqua, or shades of olive green. A druggist-style cylinder is known in brilliant teal blue, and there is a cobalt Lomax hutch from Chicago.

The quality of the glass and the workmanship of most of the bottles are comparable with that of other glass works of the time. Some of the Chase Valley product did not live up to the quality standards of the company - a common problem in piecework shops. Fortunately for collectors, some of these imperfect examples survived.

Most Chase Valley bottles found today are beer bottles without a bottler names embossed. There are several varieties of whiskey flasks and several household or druggist bottles. There are very few soda or mineral water bottles known –Hutchinson sodas and a quart soda. This confirms that the firms' strategy was to target the brewing industry. Milwaukee’s largest brewers, such as the Best, Blatz, and Schlitz breweries may have used many of the unembossed bottles. Interestingly, these companies used paper labels exclusively in the 1880’s. There are no known embossed bottles from Milwaukee from Best (Pabst), Blatz or Schlitz from the 80’s, while there are many embossed branch bottles from this era.

The market for Chase Valley Glass appears to have been primarily Wisconsin, Minnesota and Upper Michigan. There are very few marked examples from companies outside of this area. I would be interested to hear if anyone has seen Chase Valley bottles from any other states.

Today, the site of the Chase Valley Glass factories is vacant and has been extensively filled. Some years ago my wife earned big points when she called me at work to say that a backhoe was working on the Chase Valley Glass site. At lunchtime, she picked me up and drove me there. There was a large hole, about 10' deep by 10' by 30', shored up with boards. There was no one there was a ladder standing in the hole. I immediately saw glass, and moments later was picking thru a 12" layer of solid glass near the bottom of the hole, using a larger piece of glass as a trowel. It undoubtedly was a cullet pile, all broken and mostly unembossed glass from the early 1880's – virtually a was a who's who of glass works of the time - De Stieger, Chambers, Cunningham, McCully, and a very occasional Chase Valley. Unfortunately, I had only a few minutes. I got some very curious looks from the group construction workers just back from lunch when I emerged from the wet and muddy hole wearing a business suit. Unfortunately, when I returned two days later to dig I found that the hole was filled.

If anyone has new information about CVG or it’s bottles I’d love to hear from you. Peter Maas pmaas@att.net or 262-966-3473.